Cashing in Fernando Torres to fund rebuilding Liverpool can show no player is bigger than the club.

Football's most powerful clubs prosper by expelling those who no longer want to work there. The institution asserts its power over the individual. These partings can be painful, and appear calamitous, but there is always another talent out there to be hired. The club renews itself, the departing star is doomed one morning to retire.

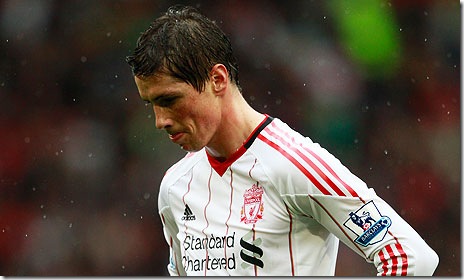

On one seismic day on Merseyside, Liverpool rejected a £35million bid from Chelsea for Fernando Torres then had a £23million offer for Luis Suarez accepted. In between, it became apparent Torres was urging Liverpool to keep listening to Chelsea, thus displaying an urge to flee Anfield for Stamford Bridge. Later he submitted a written transfer request which was rejected. In any transfer caper, the point of no return is when the player departs in his head, leaving only his body to reach for the door.

On one seismic day on Merseyside, Liverpool rejected a £35million bid from Chelsea for Fernando Torres then had a £23million offer for Luis Suarez accepted. In between, it became apparent Torres was urging Liverpool to keep listening to Chelsea, thus displaying an urge to flee Anfield for Stamford Bridge. Later he submitted a written transfer request which was rejected. In any transfer caper, the point of no return is when the player departs in his head, leaving only his body to reach for the door.

Torres is a textbook case: wanted to leave in the summer – revived that hope in January, just like Darren Bent. And when Suarez was signed on the day Torres pressed his claim, Liverpool were either moving on by acquiring a replacement or offering their Spanish star a compelling new reason not to scarper, depending on your interpretation.

Either way Liverpool were recovering their poise, their authority. For too long Anfield has fretted over this or that player absconding, as if a club with five European titles suddenly existed only to stop big names running away. The loss of Xabi Alonso and then Javier Mascherano to Real Madrid and Barcelona respectively induced a kind of rolling terror on the Kop. Those sales left Pepe Reina, Jamie Carragher, Steven Gerrard and Torres from the core of the indispensables who drove Rafa Benitez's best team to second in the Premier League with 86 points in May 2009.

When he signed, in July 2007, Torres boasted that his friends had been for You'll Never Walk Alone tattoos. In his first season he scored 33 times in 46 outings. Then he struck the winner for Spain at Euro 2008. If every centre-forward in the world bought his A game to a set of fixtures on any given day, surely Torres would be the sport's best No.9, ahead of Didier Drogba, David Villa, Diego Forlan, Samuel Eto'o, Zlatan Ibrahimovic and the rest.

Yet this is secondary to the rehabilitation of Liverpool, where a section of fans have lost all civility and consideration in their dealings with the outside world. To them, debating forums are merely a platform on which to spray abuse. Those of us who see Anfield as a bulwark against the more unedifying features of the modern game hope the anger will soon subside and the humour return.

Liverpool in Dalglish's time as a player was not splenetic, as it is now, and he would not want it to remain so. One step to salvation is to employ only those who want to be there. Torres perked up when Dalglish took over but also when the January transfer window opened to offer an escape. Courted by Manchester City in the summer, El Nino stayed at Anfield reluctantly and was not sufficiently reassured by the Fenway Sports Group takeover to reject Chelsea's overtures.

Despite the recognition that Liverpool could block the move Torres believes an immediate departure is the best solution. If he were to join Chelsea, he would be eligible to play in the Champions League. He is hopeful of Liverpool recognising that his departure could be good for all concerned. Liverpool signed him for £22million; with a little bartering they could make more than £20million profit by selling now.

Players talk hogwash about leaving "to win things". They leave mainly for money and because they tire of sharing teams with colleagues they know to be inferior. At first selling Torres seemed unthinkable. Then it started to feel like part of the recovery.

Source: The Guardian UK

Should we still keeping the player who doesn’t want to play for our club? Leave your thoughts in the comment box below.

Stay tune for more news and follow me on Twitter.

Torres has struggled since moving to Stamford Bridge for £50million from Liverpool at the end of January and has scored just three league goals in total.

Torres has struggled since moving to Stamford Bridge for £50million from Liverpool at the end of January and has scored just three league goals in total. As all the Anfield faithful has brandish him as “Judas” when he left us for the Blues. The question is “Will Liverpool’s supporters welcome him back after one year?”.

As all the Anfield faithful has brandish him as “Judas” when he left us for the Blues. The question is “Will Liverpool’s supporters welcome him back after one year?”. Former Reds striker Fowler said there was "something not quite right" about Torres' $A80 million move to Chelsea earlier this week.

Former Reds striker Fowler said there was "something not quite right" about Torres' $A80 million move to Chelsea earlier this week. Although they lost Torres Liverpool did splash out around $A95m on Newcastle's Andy Carroll and Luis Suarez from Ajax.

Although they lost Torres Liverpool did splash out around $A95m on Newcastle's Andy Carroll and Luis Suarez from Ajax. Uruguay international Suarez has a reputation for being one of the deadliest marksmen in Europe and is among a select few to have plundered more than a century of goals during his time at the Amsterdam Arena.

Uruguay international Suarez has a reputation for being one of the deadliest marksmen in Europe and is among a select few to have plundered more than a century of goals during his time at the Amsterdam Arena. Andy Carroll has completed his transfer from Newcastle United to Liverpool FC and signed a five and a half-year-deal that will keep him at Anfield until 2016.

Andy Carroll has completed his transfer from Newcastle United to Liverpool FC and signed a five and a half-year-deal that will keep him at Anfield until 2016. The club agreed a record transfer fee of £35million with Newcastle earlier yesterday for the transfer of the England international striker.

The club agreed a record transfer fee of £35million with Newcastle earlier yesterday for the transfer of the England international striker. Luis Suarez will wear the No.7 shirt for Liverpool.

Luis Suarez will wear the No.7 shirt for Liverpool. The 26-year-old had a race against time to complete a medical and finalise paperwork to seal the British transfer record deal of £50million.

The 26-year-old had a race against time to complete a medical and finalise paperwork to seal the British transfer record deal of £50million. The 29-year-old had made 18 appearances for Liverpool this season, but has been unable to win over the club's supporters.

The 29-year-old had made 18 appearances for Liverpool this season, but has been unable to win over the club's supporters.

Chelsea are willing to pay cash to bring the disaffected Torres to Stamford Bridge in what would be a record transfer between two British clubs, although not the £50million that Liverpool are seeking, which equates to the release clause in the 26-year-old contract should the Anfield club fail to qualify for the Champions League this season.

Chelsea are willing to pay cash to bring the disaffected Torres to Stamford Bridge in what would be a record transfer between two British clubs, although not the £50million that Liverpool are seeking, which equates to the release clause in the 26-year-old contract should the Anfield club fail to qualify for the Champions League this season. On one seismic day on Merseyside, Liverpool rejected a £35million bid from Chelsea for Fernando Torres then had a

On one seismic day on Merseyside, Liverpool rejected a £35million bid from Chelsea for Fernando Torres then had a  Liverpool Football Club announced on Friday afternoon that they had agreed a fee of up to 26.5million Euros with Ajax for the transfer of Luis Suarez, subject to the completion of a medical.

Liverpool Football Club announced on Friday afternoon that they had agreed a fee of up to 26.5million Euros with Ajax for the transfer of Luis Suarez, subject to the completion of a medical. Chelsea manager Carlo Ancelotti has insisted he has no plans to bid for Liverpool striker Fernando Torres.

Chelsea manager Carlo Ancelotti has insisted he has no plans to bid for Liverpool striker Fernando Torres.